Das rettende Archiv

Eine Meldung in der NMZ (Neue Musikzeitung) brachte mich darauf, den Hintergrund eines arabischen Musikers zu eruieren, der in Lissabon mit einem Preis ausgezeichnet worden ist:

Jeder Kandidat und jede Kandidatin hat jeweils 25 bis maximal 30 Minuten Zeit, sich zu präsentieren. Das sind sieben Stunden Musik an einem Tag. Das Rennen macht am Ende ein Außenseiter: Der 1983 geborene Ägypter Mustafa Said, ein blinder Künstler, der zugleich Oud-Spieler, Sänger, Musikwissenschaftler und Komponist ist.

Mustafa Saids vielfältige Karriere ist nicht ungewöhnlich in diesem Wettbewerb, die meisten der Teilnehmer sind auch Forscher, Musikwissenschaftler und Komponisten. Die Wahl der Jury ist dennoch nicht ganz unumstritten, da Mustafa Said sehr eigenwillig musiziert und ihm einige in der Konkurrenz in Sachen Virtuosität überlegen schienen. Technische Fähigkeiten stehen beim Aga Khan Music Award aber erklärtermaßen nicht im Vordergrund.

Quelle: NMZ Newsletter 23. 7. 2019 Gipfeltreffen der muslimischen Musikkultur / In Lissabon wurden zum ersten Mals die Aga Khan Music Awards vergeben / Autorin: Regine Müller / online hier

Wer also ist Moustafa Said?

Der beigegebene Text („Maqam World“ ist eine Webadresse, siehe hier) :

Maqam World says Maqam Bayati „starts with a Bayati tetrachord on the first note, and a Nahawand tetrachord on the 4th note (the dominant). The secondary ajnas are the Ajam trichord on the 3rd note, and another Ajam trichord on the 6th note. These are often used in modulation.“ Pretty technical, but the best way to learn to hear this Arabic „scale“ is to listen to a master improvise upon it. That is what Mustafa does in this video. It’s a real joy to watch and hear him as he works his artistry.

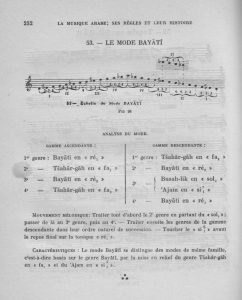

Bei Rodolphe d’Erlanger (La Musique Arabe V, Paris 1949, Seite 232 f) sieht die allgemeine Form des Maqams folgendermaßen aus:

Gut ist der Hinweis, dass die Darstellung des Maqams nicht unbedingt mit dem Grundton beginnt (d), sondern mit der Quarte (g), die echte Kadenz zum Grundton spielt Mustafa Said erst bei 1:27. Ob die zweite Tongruppe, die behandelt wird, „Tchahargah“ heißt (d’Erlanger) oder „Nahawand“ (Maqam World), hängt davon ab, ob man die Terz (f) oder die Quart (g) als Basis betrachtet. Das könnten wir Mustafa Said ablauschen…

Man findet auf Youtube noch eine Reihe schöner Aufnahmen mit Mustafa Said, rein musikalisch bezaubernd, aber visuell – als Film – meist unzulänglich. Einer der nächsten Schritte ergibt einen Blick auf das riesige Arbeitsfeld des Musikers und seiner Mitarbeiter; es ist geeignet, auch fremde Besucher für Stunden und Tage zu fesseln:

Was ist AMAR?

AMAR is a Lebanese foundation committed to the preservation and dissemination of traditional Arab music. AMAR owns 7,000 records, principally from the “Nahda” era (1903 – 1930s), as well as around 6,000 hours of recordings on reel. To safeguard this rare collection, AMAR has acquired a state-of-the-art studio specifically dedicated to the digitization and conservation of this music. In early 2010, AMAR built a multi-purpose hall that hosts up to eighty people.

The launch of AMAR took place on August 17th – 19th, 2009 at its premises in the Qurnet el-Hamra Village, Metn District, Lebanon. Two days of workshops addressed the foundation’s objectives, strategies and technical workflows. Workshops’ participants included musicologists and ethnomusicologists from Canada (University of Alberta), France (Universities Paris IV & X), USA (Harvard University), Lebanon (Antonine University and the Holy Spirit University of Kaslik), Tunisia and Egypt; all of whom form the foundation’s Consulting and Planning Board.

AMAR’s Objectives

- Conservation of recorded and printed Arab musical tradition by utilizing state-of-the-art technologies;

- Support of academic research and scientific documentation;

- Integration of these musical traditions and their practices in educational programs;

- Seeking multi-media dissemination and promotion of public awareness of the Arab music tradition.

(Fortsetzung folgt bzw. sie ist Ihnen ab sofort leicht gemacht, falls Sie es sich selbst erarbeiten wollen: beginnen Sie HIER.)

Ich werde dort fortfahren, wo ich mich zuletzt wohlgefühlt habe. Zurückversetzt in die Jahre nach 1967, als ich an meiner Dissertation schrieb und mir libanesisch-syrische Volksmusik-Formen wie Qaside, ‚Ataba oder Abou-z-zouluf anhand alter Schallplatten erarbeitete. Ich gehe also auf die folgende Seite: hier. Man sieht dort in etwa das gleiche Bild wie unten, aber anklickbar. Der grüne Balken bezeichnet den Vortrag, den man hören kann, allerdings in arabischer Sprache. Der gedruckte Text jedoch präsentiert die englische Version, darin sind die Musikbeispiele mit einer Note gekennzeichnet. Ich gebe nach den folgenden Textzitaten jeweils die genaue Zeit an, bei der man auf dem grünen Balken das Musikbeispiel abrufen kann. In diesem Fall haben wir 5 Musikbeispiele, in fabelhafter Ausführlichkeit! (Wenn alles gut gegangen ist, haben Sie den Link jetzt im externen Fenster.)

1: Furthermore some of the Syriac folk melodies chanted in church can be used to dance dabkaif accompanied by a percussion instrument. This will surely not happen because they are religious: I am not referring to the lyrics, but to the melody that is very close to the folkloric heritage melodies … MUSIK bei 10:49

2: The Lebanese Heritage Musical Forms can be separated into two main categories: those who reached us from the East, and those existing in the mountain. The heritage reached the coastal areas through the migration from the plain and the mountain. ‘Atābā (folk monadic song in colloquial Arabic), dabka or dal‘ōna only reached Beirut lately with the migration to the coast … MUSIK bei 11:58

3: Here is how the Lebanese Bekaa Bedouins we talked about sing it, accompanied by the rabāba (spike fiddle whose front is covered with sheepskin) … MUSIK bei 17:57

4: There are other styles that are also sung to the maqām bayyātī or rather the jins (set of notes forming the basic pattern in Arab music) bayyātī as there is no maqām because the scale is short … MUSIK bei 18:49

5: Here is a sample of the origin of the ‘atāba performed by the Ṭayy tribe so that our listeners can have an idea of how the ‘atāba was sung originally … MUSIK bei 25:58

(Fortsetzung folgt)