Es geht immer noch um das Rubato (JR©2010)

Der ergänzende und erweiternde Vortrag vom 18. Juni 2010

Die Titel Tr. 10 und 11 der CD, transkribiert nach der im Interview vorgetragenen Version.

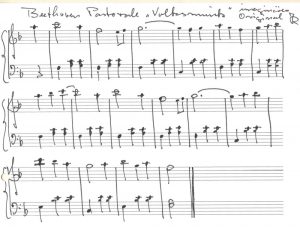

Ein Blick in Chopins Jugendzeit auf dem Lande, beginnt hier inmitten eines Briefes aus den Ferien in Szafarnia an die Familie vom 28. August 1825.

Quelle Tadeusz A. Zielinski: Chopin / Sein Leben, sein Werk, seine Zeit / Gustav Lübbe Verlag Bergisch Gladbach 1999

Es ist wohl falsch, aus der Volksmusik spektakuläre Ergebnisse für die Aufführungspraxis der Mazurken von Chopin zu erwarten. Auch die rhythmischen Verhältnisse liegen nicht immer so vertrackt, wie sie bei Janusz Prusinowski erscheinen. Dort ist es ja vor allem die rhythmische Unabhängigkeit der Melodiestimme, und der Dreier-Grundschlag ist vor allem eins: tanzbar und verlässlich, aber nicht stereotyp. Vielleicht sucht man vergeblich nach der berühmten Abweichung einer Zählzeit, weil es so selbstverständlich klingt. Um so schöner, diese CD als Ganzes zu hören, die Chopins Mazurken in das Kontinuum der Volksmusik einbezieht, wobei sie einen sehr besonderen Charakter annehmen, – was nicht besagt, dass der Komponist irgendeine Melodie 1:1 übernommen hat. Wer sich auf die Suche nach diesen Aufnahmen begibt, könnte hier beginnen.

Um den interessanten Text leichter lesbar zu machen, habe ich die englische Version abgeschrieben:

Um den interessanten Text leichter lesbar zu machen, habe ich die englische Version abgeschrieben:

In spite of intense efforts of musicologists have not been able to solve the problems of the use of folk music quotations in the works of Chopin. The composer did not refer directly to folk tunes but composed in the characteristic mood of this music. The main factor of identifying Mazurkas as musical pieces growing out of the Polish folk music was the mazurka rhythm. Heard in the Ukraine, Moravia, Lusatia and all over Scandinavia nowhere is it as wide spread as in central and western Poland. The mazurka rhythm is considered as a determinant of Polish character in music. It is used in the whole familiy of dances in triple meter which roots back in the Polish Renaissance and Baroque time.

This family consists of dances of different choreotechnic structures and tempo of performance, the slowest being the chodzony (walking dance), faster Kujawiak, followed by mazurka and finally the fastest of them all – oberek.

Distinction of the last two dances is often a difficult task. In some regions of Poland (e.g., the voivodship of Radom) the name commonly used is „oberek“ while „mazur“ is used as an alternative term for „sung oberek“ generated from vocal background. To simplify matters it is acceptable to consider the fastest of the round dances as oberek. The slower ones can be locally qualified as either oberek or mazurka.

Separate from the folk tradition but growing out of the folk mazurka a national mazur came to being. In comparison with the folk one, the national mazur is characterised by a much higher accumulation of dotted rhythms. From the end of 18th C. Mazurka entered into a canon of piano and stage music finding fulfilment in the compositions of Chopin.

However having taken a closer look at Chopins Mazurkas it is possible to discover a mixture of different traditions with a stress on the national mazur and the old Kujawiak. The name „Kujawiak“ appeared the first time in 1827. This widespread dance takes its region of Kujawy but the name is probably not a folk name. During the 19th C. a certain style of Kujawiak was formed and popularised. During that period of time, due to the moderate tempo and domination of minor scale a stereotype of a Kujawiak as a melancholic tune was formed.

Traditional folk Kujawiak is a pair round dance, however in comparison with other Polish round dances it lacks spontaneity. It exists in two versions differing from one another by its tempo and the direction of the turn. Ksebka is a left turn dance which is also sometimes called a „slow“ Kujawiak. Odsibka is a right turn dance, a bit faster and often considered to be the „proper“ Kujawiak. Both of theses dances were a part of the traditional cycle of triple meter dances with a progressively growing tempo which were called in the region of Kujawy „okragly“ (the round one). This cycle, often based fully on one medlody was formed by chodzony (walking dance), slow Kujawiak (called also the „sleeping“ one), the proper Kujawiak, mazur or obertas. Lyrical load present in Chopins Mazurkas seems to have its source precisely in the folk Kujawiak.

In our view Mazurkas are closely connected to pure folk music, so the mixture of both groups of repertoire and their performance by the some group of instruments has been considered by us as a natural way of things.

Ewa Dahlig / Maria Pomianowska

Erst jetzt habe ich einen im Internet abrufbaren Text von Dr. Ewa Dahlig-Turek entdeckt, in dem viele Probleme behandelt sind, die man ohne kundige polnische Hilfe nicht lösen kann. An dieser Stelle zunächst nur das Abstract, alles weitere dort.

Although Chopin’s music is continually analysed within the context of its

affinities with traditional folk music, no one has any doubt that these are two separate musical worlds, functioning in different contexts and with different participants, although similarly alien to the aesthetic of mass culture. For a present-day listener, used to the global beat, music from beyond popular circulation must be “translated” into a language he/she can understand; this applies to both authentic folk music and the music of the great composer.

In the early nineties, when folk music was flourishing in Poland (I extend the term

“folk” to all contemporary phenomena of popular music that refer to traditional mu-

sic), one could hardly have predicted that it would help to revive seemingly doomed

authentic traditional music, and especially that it would also turn to Chopin. It is

mainly the mazurkas that are arranged. Their performance in a manner stylised on

traditional performance practice is intended to prove their essentially “folk” character. The primary factor facilitating their relatively unproblematic transformation is their descendental triple-time rhythms.

The celebrations of the bicentenary of the birth of Fryderyk Chopin, with its

scholarly and cultural events of various weight geared towards the whole of society,

gave rise to further attempts at transferring the great composer’s music from the

domain of elite culture to popular culture, which brings one to reflect on the role that

folk music might play in the transmission and assimilation of artistic and traditional

genres.

1810 * Chopin. „Bicentenary“. Ob mir das überhaupt klar war? Jetzt dürfte also posthum die Lektüre der ganzen Original-Arbeit folgen, die ich damals (2010) verpasste, als ich mich aufs neue für das Mazurka-Thema begeisterte. Sie soll mich eine Weile beschäftigen, ebenso wie die CD, von der ich nicht weiß, wie sie schon viel früher den Weg zu mir fand.

(Fortsetzung folgt: siehe die schon angegebenen Links: hier und nochmals dort)

* * *

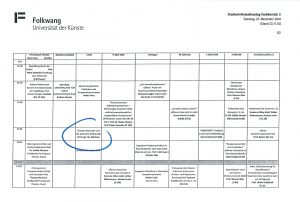

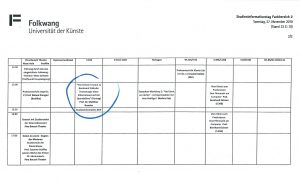

Wann war es nun? Wo begann es? Mit der Tacet-CD gewiss und dann … im Juni oder November 2010, womöglich sogar zweimal? Deutlich in Erinnerung jedenfalls: der anschließende, spannende Vortrag von Prof. Brzoska (Stichwort Einführung der Gasbeleuchtung im Theater). Er gehörte auch zu meinen wenigen Zuhörern und sagte, er habe nicht gewusst, dass man an Chopin noch musikethnologische Studien betreiben könne. Jedenfalls empfand ich es als Lob.

Brzoska s.hier

Brzoska s.hier

Varianten der Mazurka. Der heutige Tag wurde gekrönt durch Varianten eines Abendrots, das mich vom Schreibtisch an das Fenster des Arbeitszimmers und hinaus auf den Balkon zog. Ich möchte mich daran in Zukunft erinnern, wenn ich wieder gutgelaunt im Keller sitze und … die einschlägigen Chopin-Mazurken am Flügel durchgehe. Oder sogar wieder ernsthaft übe. Mit der letzten beginnend.

Der Abend kommt ab 17.08 Uhr (10. November 2022)

ZITAT (Zielinski)

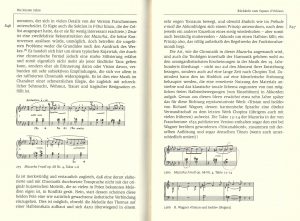

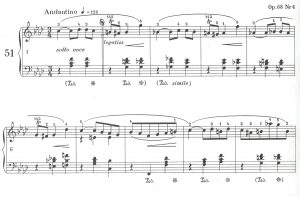

Die letzte Komposition, die Chopin überhaupt geschrieben hat, ist die Mazurka f-moll (op-68 Nr.4). Allerdings war der Komponist nicht mehr imstande, sie zu vollenden, und hinterließ sie in einer recht unklaren, mit vielen Streichungen versehenen Skizze. Zunaächst meinte man, das Manuskript sei nicht mehr zu entziffern und nur für den Komponisten verständlich gewesen, doch gelang es Franchomme unter Aufwendung großer Mühe, das Werk zu entschlüsseln, und trotz einiger nicht mehr zu klärender Details erschloß er damit ein Werk von außergewöhnlicher Schönheit und Ausdruckskraft. (Ein neuer, von der Skizze des Komponisten ausgehender Rekonstruktionsversuch wurde 1965 von Jan Ekier vorgenommen, der sich in vielen Details von der Version Franchommes unterscheidet. Er fügte auch die Sektion in F-Dur hinzu, die der Cellist ausgespart hatte, da er sie für wenig interessant erachtete.)

Quelle Tadeusz A. Zielinski: Chopin / Sein Leben, sein Werk, seine Zeit / Gustav Lübbe Verlag Bergisch Gladbach 1999

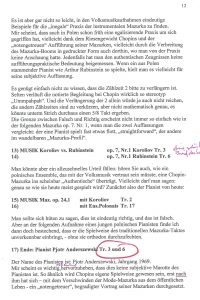

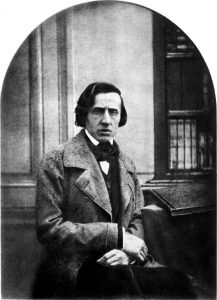

Chopin, erstes (und letztes) Foto 1849

Chopin, erstes (und letztes) Foto 1849

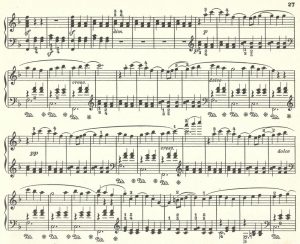

Koroliov spielt genau die kürzere (2:29) Fassung, die in meiner Ausgabe des Fryderyk Chopin Instituts (Paderewsky) 16. Edition Cracow 1979 steht. Rubinstein spielt die Version, die einen – den – F-dur-Mittelteil enthält (3:15).